The enduring network of Britain’s civic buildings – from grand town halls and libraries to museums and courthouses – is more than an architectural legacy. These structures form *essential social infrastructure*. The future resilience of the UK’s urban and municipal governance hinges upon the successful preservation and strategic adaptation of this estate. In this article, I examine the historical significance of the civic estate, the conservation challenges we face today, and the strategic imperative for renewal. I argue that investment in the civic estate is not a discretionary cultural expenditure but a foundational driver of sustainable economic development, social cohesion and climate mitigation.

The built fabric of civic life in the UK charts the evolution of democracy, municipal ambition and public service. From the ornate expressions of 19th‑century confidence to the utilitarian structures of the post‑war era, civic buildings reflect the changing role of local government and public identity.

1.1 The Golden Age of Civic Pride (Victorian and Edwardian)

The mid‑Victorian era represented a golden age of civic architecture. Town halls, libraries and museums proliferated as municipalities sought to manifest their growing wealth and civic self‑confidence. Style became a statement. Two dominant trends were:

* The grand, formal Classical revival – emphasising symmetry, monumental scale, and an overt statement of civic gravity.

* The picturesque but academically grounded Gothic revival – richly ornamented, vertically oriented, with pointed arches and dramatic silhouettes.

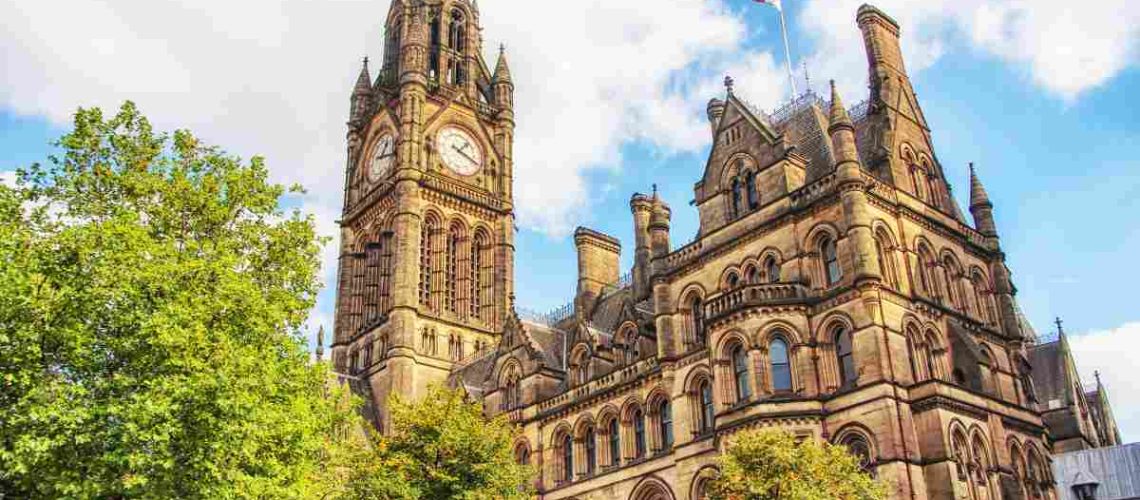

A definitive example of this civic ambition is Manchester Town Hall (1868–77) designed by Alfred Waterhouse. This Grade I listed building remains one of the UK’s finest manifestations of Neo‑Gothic architecture. Waterhouse’s genius lay in planning the irregular triangular site to combine monumental ceremonial spaces (a large public hall, reception suites) with the practical work of the expanding municipal corporation, including innovations like a warm‑air heating system. The exterior was detailed to embody civic identity: sculptures of historical and symbolic figures underscoring the seriousness of municipal life.

With the Edwardian period came a shift: designs became less cluttered, lighter in palette, simpler in pattern, reflecting aesthetic tastes evolving away from soot‑laden Victorian streets and the gradual arrival of gas and electric lighting.

1.2 The Post‑War Paradigm Shift and the Brutalist Reckoning

The second central inflexion point arrived in the post‑war decades. Wartime devastation and the economic imperative of reconstruction ushered in a radically different civic architecture paradigm: functional, bold, and often austere. Prominent among these was the Brutalist aesthetic: raw materials (typically unpainted concrete), block‑like massing, exposed structural and service elements, little ornamentation – form strictly following pragmatic function.

Many of these structures have since entered public debate as unwanted relics: demonised in demolition discussions as symbols of civic austerity or functional failure. Yet the public narrative surrounding their destruction is often incomplete: though politicians or developers may claim residents “hated the place”, interviews with those who lived or worked in such developments reveal that many did *enjoy* or appreciate the space. The push to demolish was often driven by political, aesthetic or commercial motives rather than purely social failure. This dynamic shows that conservation challenges in post‑war civic estates are as much about power, politics and perception as about bricks and mortar.

Today, these buildings are being re‑evaluated (sometimes quite critically) in light of the climate imperative: retaining existing structures is increasingly recognised as essential to carbon‑reduction and resource‑efficiency strategies.

1.3 Architecture and the Social Contract

Civic architecture has always done more than house bureaucracy: it has shaped community identity and delivered social policy. Consider the early public libraries in the UK (following the Public Libraries Act 1850). These were often founded with a specific social mission: to “civilise” what was then considered the dangerous classes by offering an alternative to rough recreation such as dog‑fights or the gin‑shop. Over time, the civilisation of the masses became a municipal goal, expressed in brick, stone, and iron.

This tradition has evolved into the modern conception of libraries as inclusive community hubs. Today, libraries are documented to contribute to multiple critical outcomes: cultural enrichment, improved literacy, digital access, better health and happiness, and stronger, resilient communities. The historic function of the civic estate as an instrument of public good means the case for strategic investment in these buildings transcends culture alone—it extends into economic development, social care, digital inclusion and place‑making. In other words, civic buildings are cross‑functional social infrastructure.

When we look at civic renewal not as a cost, but as an investment, a picture emerges of significant return: social return through community cohesion and wellbeing; economic return through regeneration, employment and built‑heritage value.

2.1 Quantifying Community Cohesion and Wellbeing

Civic and community buildings sit at the heart of collective identity. They foster pride, provide a sense of belonging, and a place where citizens can meet, interact, and collaborate. The creation of social value comes through engaging local people: the process matters as much as the building.

Research shows a direct, quantifiable benefit to personal health and wellbeing derived from engaging with heritage. Visits to historic sites—especially towns and buildings—have the most significant positive impact on wellbeing. For example, the estimated monetary value of the average effect of heritage visits on wellbeing is approximately £1,646 per person. Given that civic buildings contribute directly to outcomes like healthier lives and stronger communities, the social dividend adds a compelling dimension to the investment case

2.2 Heritage as an Economic Multiplier

The historic environment is a significant component of the UK economy. In England, the heritage sector contributed over £11.9 billion in Gross Value Added (GVA), equating to about 2 % of national GVA. The repair and maintenance of historic buildings themselves generate substantial construction sector output (valued at £9.6 billion). Investment in landmark places generates strong economic returns for the surrounding area: on average, £1 of public expenditure dedicated to heritage‑led regeneration generates £1.60 in additional economic activity over a ten‑year period.

The converse is telling: listed buildings across the UK face an estimated £2 billion maintenance shortfall. Considering that maintenance expenditure supports billions of construction output and employment, this shortfall represents a quantifiable loss of potential economic stimulus and employment. In effect, strategic investment in civic estate repair and adaptive reuse is a potent instrument of industrial policy.

Historic properties aren’t just “old buildings” – they are active centres of commerce: in the UK, some 138,000 businesses are located in listed buildings, contributing £4.7 billion to economic output.

Headline metrics showing why civic heritage renewal must be treated as strategic:

Heritage Sector Annual GVA (England): £11.9 billion.

Economic Return on Regeneration: £1 public spend → £1.60 additional activity over ten years.

Operational savings example (Lambeth Town Hall consolidation): £4.5 million annual taxpayer savings.

Carbon reduction via adaptive reuse (vs new build): potential reductions of over 60 % of CO₂ emissions.

Potential economic output from heritage retrofitting: £35 billion annually.

These figures make clear: renewing the civic estate isn’t optional—it is financially sensible, environmentally responsible, and socially necessary.

Despite the strong case, practical implementation is hindered by systemic hurdles: funding shortfalls, regulatory complexity, skills gaps.

3.1 The Maintenance Deficit and Financial Vulnerability

The £2 billion maintenance backlog for listed buildings is a critical barrier to renewal. Many of the civic heritage assets now operated by local authorities or third‑sector partners are financially vulnerable: reliant on self‑generated income, visitor footfall, and charitable giving. Economic shocks (such as the pandemic) depleted reserves and led to staffing reductions across 40 % of heritage organisations.

A significant barrier is taxation: current VAT rules on maintenance reduce available spend for essential repairs by almost a fifth. This is economically counterproductive. Given the strong return on investment from heritage‑led regeneration, the imposition of VAT on vital repair work prioritises short‑term tax revenue over long‑term economic stimulus and asset preservation. For example, expanding existing grant schemes (e.g., for places of worship) to include free‑entry attractions could cost about £6 million but yield an estimated £7 million economic benefit by unlocking necessary repairs and increasing access.

3.2 Navigating the Regulatory Landscape and Funding Streams

Addressing the maintenance gap requires cleverly deploying funding mechanisms and planning tools. One of the most effective strategies is adaptive reuse—finding a viable new use for heritage buildings that secures long‑term sustainability and removes them from the risk register (e.g., Historic England’s “Heritage at Risk” list).

Financial assistance comes from major streams such as the National Lottery Heritage Fund (grants of £10,000-£10 million) and Historic England funding for urgent repairs and local authority-led projects. These grants not only provide capital but also enforce adherence to traditional materials, skilled craftsmanship, and conservation best practices.

Local authorities face a policy tension: on one hand, they need to pursue efficiency savings (service rationalisation, estate consolidation); on the other, they have a social mandate to maximise community resilience and inclusive local access (particularly in deprived areas). Successful strategies, therefore, require co‑location, hybridisation (e.g., community hubs combining library, civic services, coworking, health), rather than closures. The aim: achieve efficiency without undermining the social purpose of the civic estate.

Adaptive reuse is the central strategy for civic renewal. It reconciles the imperative to preserve architectural heritage with the urgent demands of sustainability, accessibility and changing civic function.

4.1 The Environmental Imperative (Embodied Carbon)

From an environmental standpoint, the most sustainable building is the one that already exists. The construction industry is a major generator of waste and emissions—some estimates suggest up to 60 % of the UK’s waste comes from construction, demolition and excavation activities. Demolishing a building not only loses its embodied carbon (the CO₂ locked into original materials and construction) but forces new construction, which itself must “pay back” that embodied carbon via operation.

By retaining and retrofitting existing structures, we can reduce CO₂ emissions by over 60 % compared to demolition and new build. That elevates heritage preservation from cultural preference to core national

infrastructure policy—essential for local authorities working towards net‑zero targets.

4.2 Achieving Net‑Zero in Historic Fabric

Retrofitting historic civic buildings demands adherence to the energy hierarchy: Be Lean → Be Clean → Be Green. The first step, ‘Be Lean’, means maintaining the building properly. Many historic structures are more than a third less energy‑efficient if suffering from damp, decayed fabric, failing rainwater drainage or poorly maintained windows. Thus preserving the building in good repair is the most cost‑effective action.

4.3 Ensuring Universal Accessibility (DDA Compliance)

Access is both a legal and moral mandate. Under the Disability Discrimination Act 1995 (DDA Part III), owners and managers of historic properties with public access must provide barrier‑free access “to the extent that is reasonably achievable”, accounting for conservation constraints. Historic civic buildings often feature levels, changes of floor, narrow stairs and heritage‑protected fabric. Standard solutions rarely suffice.

The key is bespoke, discreet interventions: platform lifts, compact step lifts, semi‑permanent ramps meeting British Standard gradients (maximum 1 :12) that respect the building’s story. Combining accessibility with conservation, the adaptations must preserve character while fulfilling the modern requirement of inclusive access.

Ensuring the longevity of civic heritage requires thoughtful adaptation rather than replacement. By applying sensitive, evidence-based interventions, it is possible to enhance comfort, safety, and energy performance while retaining the architectural and cultural integrity that defines these spaces.

The table below outlines practical strategies for improving the performance and accessibility of historic civic buildings in line with modern expectations—without compromising their original fabric or historic value.

| Challenge Area | Conservation Strategy | Implementation Example | Technical Justification |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Efficiency (Thermal Loss) | Preserve Historic Fabric; Adhere to “Be Lean” principle | Installation of customised, discrete secondary glazing systems. | Achieves performance similar to double-glazing without structural modification or listed building consent requirements. |

| Physical Accessibility (Mobility) | Provide barrier-free environment (DDA 1995) | Custom-designed, compact platform lifts or elegant step lifts. | Respects conservation requirements while ensuring legal and ethical access for all users without compromising the building’s story. |

| Structural Integrity & Durability | Maintain traditional building physics and moisture regulation | Use of compatible, traditional materials (e.g., lime plaster, matching stone). | Prevents moisture trapping, decay acceleration, and failure associated with modern, incompatible materials. |

Successfully bridging the past and the future requires a clear strategy: combine conservation discipline with modern functionality, energy performance and inclusivity.

5.1 Town Halls: Consolidation and Carbon Reduction

The restoration of the Grade II-listed Lambeth Town Hall and adjacent Civic Centre provides a blueprint.

The project consolidated the council’s core office buildings from 14 down to just two, achieved a one‑third reduction in carbon footprint and delivered £4.5 million annual taxpayer savings.

This shows how strategic retrofit of the civic estate can deliver fiscal, social and environmental benefits in parallel.

5.2 Libraries: Evolution into Mixed‑Use Hubs

Libraries are evolving from pure book‑lending enterprises into multi‑service community hubs, co‑located with gyms/spas, coworking, health, and digital services.

One example is the South Woodford library and gym model. This diversification improves access to services, drives footfall, and delivers efficiency savings for local authorities. In this way, the civic estate responds to 21st‑century municipal demands while preserving heritage.

5.3 Heritage for Housing and Regeneration

Vacant historic buildings can be transformed into mixed‑use schemes—heritage conversion into housing, commercial, and community space. According to Historic England’s assessment, repurposing and repairing these sites could provide between 560,000 and 670,000 new homes—meeting 37–45% of the government’s 1.5 million housing target by 2029. This approach addresses housing shortage, preserves heritage and stimulates regional economies while supporting low‑carbon growth.

One of the primary constraints preventing full realisation of the civic renewal strategy is the critical shortage of specialist conservation skills.

6.1 The Critical Skills Shortage and Economic Constraint

The retrofit of the UK’s historic buildings can generate £35 billion in economic output annually and create substantial construction‑sector employment. Yet the UK currently has only half the skilled workers needed to execute this retrofit work. Nearly 47 % of heritage industry practitioners cite the skills gap as a significant concern. 11 % of heritage firms in England report workforce skills gaps; 4 % of workers are not fully proficient; and 1.1 % of all jobs are vacant due to skills shortages. This market failure—the inability to scale the workforce—actively limits the speed and quality of conservation projects, thus obstructing both national economic stimulus and climate goals.

6.2 The Science of Traditional Materials and Conservation Practice

Proper renewal demands specialist knowledge of building physics: old buildings “breathe” and regulate moisture in ways modern buildings do not. The choice of materials is not aesthetic, but a long‑term survival decision. Incompatible modern materials (e.g., cement‑based mortar applied to historic brickwork) can trap moisture and accelerate decay. Conservation walks the fine line between preservation and adaptation; for this reason, professionals must deploy traditional techniques and materials (lime plaster, original masonry, period woodwork) to ensure authenticity and durability.

Collaboration is essential: local authority Conservation Officers, conservation‑accredited architects, surveyors, and engineers working via professional bodies like the Institute of Historic Building Conservation (IHBC), the Royal Institute of British Architects (RIBA) and the Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) ensure that the repair is both compatible and effective.

6.3 Pathways to Proficiency

The imbalance in training is stark: most construction vocational programmes focus on modern methods, leaving the heritage sector to scramble for skilled craftspersons. Targeted programmes are needed: for example, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings (SPAB) Fellowship and William Morris Craft Fellowship provide training for craftspeople working on historic buildings. Historic England supports bursary‑funded training programmes for individuals with general construction training who wish to transition into heritage work, gaining experience under existing craftspeople and working towards a Level 3 NVQ Diploma in Heritage Skills (Construction).

The civic estate is indispensable to the UK’s social, economic and environmental future. From the Neo‑Gothic town halls of Victorian ambition to the often‑contested post‑war blocks of municipal austerity, Britain’s public buildings are at a tipping point: transitioning from symbols of historical achievement to engines of modern resilience.

The evidence is firmly on the table: renewing these assets is fiscally responsible, socially necessary and environmentally imperative. We have clear indications of high returns on investment (e.g., £1 spent → £1.60 additional activity) and tangible operational savings (e.g., £4.5 million per year in Lambeth). And we have a climate imperative: adaptive reuse can reduce embodied carbon by more than 60 %, making heritage renewal a meaningful contributor to net‑zero agendas.

But the full potential of this renewal strategy is currently held back by systemic constraints:

Policy reform is needed to resolve the paradox of tax burdens (such as VAT on repairs) that hinder maintenance expenditure and exacerbate the £2 billion backlog.

Skills investment is vital to bridge the workforce gap and enable the predicted £35 billion-plus in annual economic output from heritage retrofit to be realised.

For us at Tuscan Foundry Products, our experience since 1893 in providing traditional cast‑iron rainwater systems, bespoke castings and heritage‑sensitive products means we understand exactly how the technical side of this challenge connects with the bigger strategic narrative. Our work helps ensure that the details—gutters, downpipes, drainage systems—do not become the weak link in a heritage renewal strategy. Rather, they become part of a holistic approach to conserving, adapting and revitalising the civic estate.

In short, reclaiming our civic heritage is not an optional cultural exercise; it is a strategic investment in civic resilience. It is about place, purpose and performance. It is about ensuring our public buildings continue to serve communities, drive economies and reduce carbon for generations to come.

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What exactly is meant by the “civic estate”?

The term refers to the ensemble of publicly owned or publicly accessible built assets—town halls, libraries, museums, courthouses, civic centres, and sometimes major community hubs—that perform public service and governance functions. These are more than buildings: they are part of municipal infrastructure and social fabric.

2. Why should local authorities prioritise heritage buildings when there are pressing service delivery demands?

Because heritage buildings are not simply decorative—they are essential social infrastructure that deliver measurable returns: social wellbeing, economic regeneration, job creation and climate mitigation. Investment here is part of long‑term sustainable service delivery, not a distraction from it.

3. What is adaptive reuse and why is it essential for the civic estate?

Adaptive reuse means repurposing existing buildings (often historic) for new uses while retaining their fabric. For civic estate renewal, this enables buildings to accommodate changing needs (digital hubs, community services, co‑working) while preserving heritage and achieving environmental savings (embodied carbon, resource reuse).

4. How significant are the environmental benefits of re‑using heritage buildings?

Very significant. Retaining and retrofitting existing structures can reduce CO₂ emissions by over 60 % compared to demolition and new build. Moreover, it avoids the embodied carbon cost of new construction and makes the most of existing assets.

5. What are the main barriers to renewing the civic estate?

Key barriers include: significant maintenance backlogs (estimated £2 billion for listed buildings in the UK), tax and regulatory inefficiencies (for example VAT on repairs), the skills shortage in heritage crafts and conservation, and the challenge of aligning diverse funding streams and stakeholder priorities.

6. How can local authorities improve accessibility in historic civic buildings?

They can adopt bespoke, low‑intrusion solutions such as platform or step lifts, semi‑permanent ramps (meeting British Standards), secondary glazing rather than wholesale window replacement, and materials compatible with heritage fabric. A clear audit of access constraints and engagement with specialist conservation and accessibility consultants is vital.

7. What role can a specialist company like Tuscan Foundry play in civic heritage renewal?

As a specialist heritage supplier (since 1893) of cast‑iron gutters, downpipes, bespoke castings and traditional drainage systems, Tuscan Foundry provides the technical, material and craftsmanship support that ensures historic buildings retain integrity while being adapted for modern needs. We help ensure the detailed infrastructure supports the broader strategic investment in civic estate renewal.

—

The invitation is clear: the civic estate deserves investment, strategy and care. At Tuscan Foundry, we are proud to play our part in ensuring that Britain’s civic heritage remains vibrant, resilient and relevant for the future.