The term ‘dampness’ is used in the context of buildings to refer to the presence of excessive moisture that, if not addressed, may harm them or their occupants.

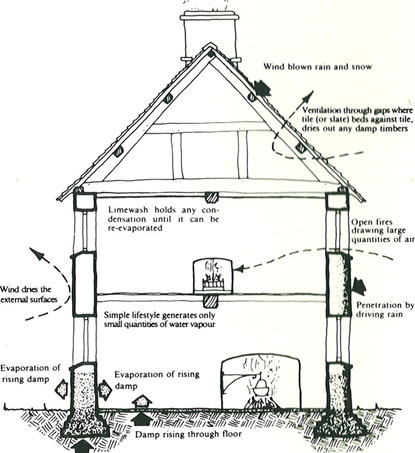

The source of this moisture can be either liquid water or water vapour in the air. Buildings remain dry when water from various ‘moisture sources’ (for example, moist, warm air rising out of a bath) is balanced by its dissipation via ‘moisture sinks’ (such as good ventilation for a humid bathroom) or storage in ‘moisture reservoirs’ (for instance, absorbent materials). If this equilibrium is upset, however, buildings may become damp

To understand how this equilibrium arises in older buildings, it is necessary to consider first the way they are built.

Pre-c1919 buildings are typically of ‘traditional’ construction. They tend to have solid walls, and sometimes solid floors, built using ‘breathable’ materials that allow the free passage of moisture. 2 These include stone, soft brick, unfired earth,

lime-based mortars and plasters, and lime wash. They take in more moisture than their modern substitutes but allow it to evaporate readily when conditions become drier.

As well as being of traditional construction, many older buildings are vernacular (indigenous) in nature so possess features adapted for the local climate. The UK’s maritime climate means that pitched roofs to shed water quickly are usual, generally with gutters and downpipes or otherwise generous overhanging eaves.

During rain, a certain amount of moisture deposited on the outer face of a solid wall will be taken in by capillary action and seep slowly inwards. The vapour permeability of the building fabric will enable this moisture to be drawn back to the surface and evaporate when the rain has stopped, before it can reach the inner face, although extra protection is sometimes required.

Various traditional methods exist to give walls extra protection from the rain with little hindrance to evaporation. These include the application of lime render, comprising roughcast (or harling) in more exposed regions, with limewash.3 Slate-hanging is an alternative seen in the south-west and tile hanging in the south-east. Weatherboarding is associated with the south-east and parts of East Anglia. Good weatherings are important, too, such as projecting cills, stringcourses, hood moulds and pentice boards (see figure 3). Internally, solid walls can be lined with lath and plaster on timber battens to create an air gap that reduces the likelihood of moisture penetration.

Most pre-c1919 buildings were built without damp-proof courses (DPCs) or damp-proof membranes (DPMs) to act as barriers to moisture in walls and floors respectively. Moisture will rise to some degree as it is drawn by capillary action into the pores of permeable materials, such as brick or stone, that are in contact with damp soil. This is usually not a problem where the construction can ‘breathe: allowing evaporation.

The absorbed moisture will rise in a wall to a height at which there is a balance between the forces of capillary rise and that of gravity and evaporation.

This height will vary somewhat with the time of year, wall thickness, pore size and the level of the water table in the ground. Flagstone or brick floors used to be laid directly upon the bare earth and the moisture that rose through these floors would be carried away by ventilation (see figure 4). Additionally, the hygroscopic nature of many traditional building materials means they absorb small quantities of moisture from the air when it is humid and rerelease it under drier conditions.

Old buildings are not inherently damp. Before central heating was commonplace, they were heated by open fires that drew in large quantities of air through loosely fitting windows and doors. Generally, this high rate of ventilation would have quickly evaporated ‘structural moisture’from the breathing fabric internally while such moisture on external wall surfaces would be driven away by the wind. There was, therefore, in theory, an inherent equilibrium.

In practice, this equilibrium may be upset for various reasons with the consequence that liquid water persists for long enough to adversely affect the physical structure of materials, or that relative humidity increases to a detrimental level of 70% or higher. Where dampness exists, it should not be ignored. Although a decision may be taken not to carry out any remedial work, this should only be made after the dampness has been investigated carefully.

This Technical Advice Note considers next the sources and symptoms of dampness, along with its causes (sections 2 and 3). Understanding these is an important prerequisite for diagnosing, controlling and preventing dampness problems (sections 4 to 7).