It is important to understand the causes of dampness problems, as well as their signs and symptoms, because this will help when it comes to implementing effective control measures.

Addressing the cause of dampness is always preferable, where possible, to dealing merely with the symptoms.

Neglect (especially where access for maintenance is difficult), deterioration and vandalism are commonly associated with rainwater penetration. (See figures 12a and 12b.) Problems will be most acute during prolonged spells of heavy rain.

Leaves, moss and dirt can build up quickly in gutters and hopper heads, obstructing the free passage of water and causing leakage or overflow. Leaks from parapet and valley gutters are particularly serious because the spaces beneath tend to be warm, poorly ventilated and contain the bearings of the roof trusses. In these conditions, water from blocked or defective parapet/valley gutters can give rise to severe fungal growth.

Cracked hopper heads or downpipes, especially where the crack may be undetected against the wall, are another source of dampness in walls. A downpipe will often become choked with leaves, causing water to back up the pipe and spurt out of the joints or cracks onto the adjacent wall. Such concentrated and continued wetting is likely to erode mortar joints, corrode fixings (potentially leading to further failure), promote moss growth externally, which prolongs the dampness by retaining moisture, and may also lead to frost damage. (See figure 13.)

Defective drains or gulleys, or leaking water pipes can add considerably to the moisture-load of the ground in proximity to the base of walls. Often problems of rising dampness are caused by failures of this nature rather than the presence of ground water per se.

Driving rain can penetrate even a thick wall through weak points, such as cracks and open joints. Roofs, chimneys and parapets, normally being the most exposed parts of a building, are particularly susceptible to rainwater penetration. Something as straightforward as a displaced tile or defective flashing or mortar fillet can cause significant damage. Water may also be drawn by capillary action through cracks in leadwork.

Traditional and modern buildings handle moisture in different ways and mixing the two types of construction can cause dampness. Unlike older, traditional construction with solid walls and

floors that rely on the need to ‘breathe’ to stay dry, modern buildings are normally built with cavity walls and floors that employ’vapour closed’ materials of low permeability, for example, ordinary Portland cement. They depend on excluding water with barriers and moisture breaks. The two types of construction are like overcoats and raincoats respectively. Old buildings usually become damp when barriers to moisture are added. New buildings, on the other hand, become damp when such barriers fail.

Any impervious covering, such as linoleum, vinyl etc, laid over a solid ground floor in contact with the ground will become soaking wet underneath and problems may also follow the installation of a DPM. Water trapped under the floor could be forced up the walls and, where there is no DPC, cause rising dampness there. The installation of a DPM in the floor of a cob, wychert, clay lump or other earth-walled building can increase dampness in the walls to such a degree that they collapse.

Attempts to seal walls (for example, with dense plasters, polyvinyl acetate (PVA) or impervious paint) will impede the evaporation, trapping moisture or displacing it elsewhere, and can lead to spalling or powdering of surfaces.7 (See figures 14a and 14b.) The use of impermeable plastic-based materials for decoration and repair also results in more humid internal environments and tends to encourage condensation.

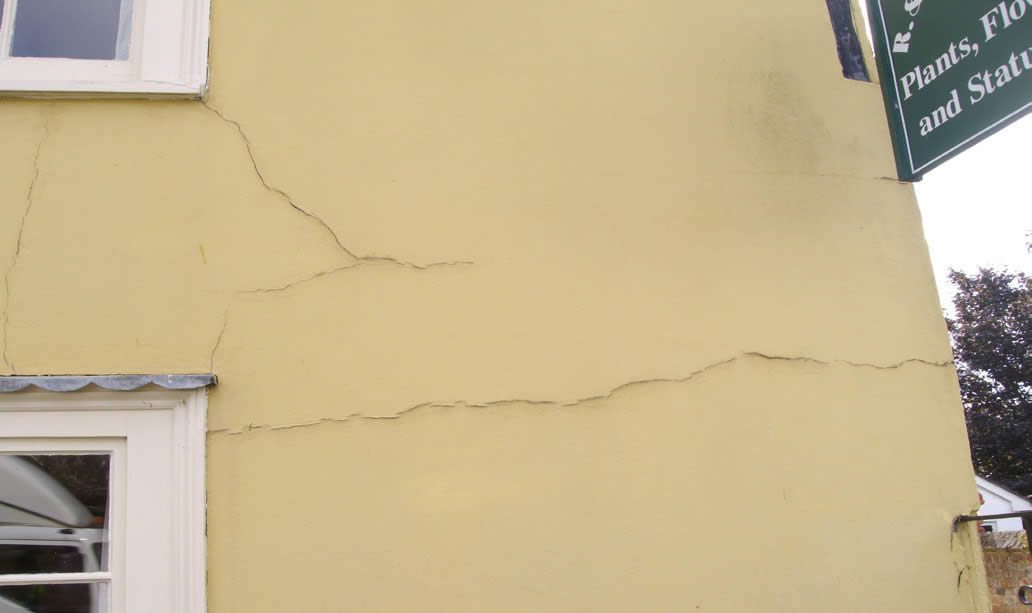

Modern cement renders and pointing are brittle, of low permeability and tend to crack easily as walls undergo small thermal or structural movements (see figure 15). Water commonly streams down the surface of such render and is drawn into fine cracks by capillary action where it becomes trapped.

Consequently, moisture may build up behind the render and eventually find its way to the inside face.

Using hard cement renders, vapour barriers or impermeable thermal insulation on walls also increases the likelihood of interstitial condensation. Cement renders hinder the evaporation of moisture in the wall from the external surface. In certain solid walls at specific times of the year, moisture bound within the wall fabric may evaporate from both the external and internal wall faces. For these walls, the inclusion of a vapour control layer (VCL) close to the internal wall face will restrict the amount of moisture accessing the surface for evaporative purposes and may cause moisture to accumulate in the masonry of the wall. This is also likely with internally insulated walls that incorporate a VCL.

Other inappropriate work includes the stripping of lime render from buildings – a practice long opposed by the SPAB and which lead to its early nickname of the Anti-Scrape Society.

Compared to their modern counterparts, older buildings require greater ventilation to remove structural moisture from their breathing fabric, in addition to the water vapour generated by the activities of their occupants. Even though old buildings are often overgenerously ventilated, excessive draughtproofing and the installation of double-glazing has contributed to an increase in condensation problems in recent years. Ventilation levels should not be reduced excessively (to below 0.4-0.5 ach). 8

Chimney flues can become damp through condensation because modern boilers and closed stoves draw in considerably less air than open fires. The warm humid flue gases rise slowly and are likely to condense on any part of the flue which is exposed or has poor thermal insulation. Disused flues may also suffer from condensation if they are closed off without adequate ventilation at the top and bottom.

Experience shows bitumen-coated fabric on the outside of roofs or spray-on coatings underneath prevent proper inspection, hinder the reuse of slates or tiles and, by reducing ventilation, increase the risk of timber decay. They are a false economy, and cases have been reported of serious damage resulting to the structure. These treatments can adversely affect the mortgageability of properties.

The blocking up of subfloor vents may lead to condensation problems and serious timber decay in the associated voids.

Our modern, more sedentary, interior lifestyles have changed the moisture equilibrium in old buildings. Internal room moisture is increased by cooking and washing activities (such as drying laundry, boiling kettles and bathing) that can distribute more moisture into rooms.

Condensation may occur in a thick-walled or solid floored building of high thermal capacity, such as a church, if it is heated intermittently, particularly where moisture-generating flueless bottled gas stoves and heaters are used. (See figure 16.) The heating installation does not have time to warm the surfaces above the dewpoint temperature, so moisture from the already warmed air condenses on them. (A rapid change from cold to warm, humid weather can produce a similar effect.)

Additionally, where patios, paths and other hard surfaces are laid up to walls, inadequate drainage or rainsplash commonly soaks them.

Moisture movement can increase when central heating is first installed or turned on after the summer months: sometimes soluble salts are drawn to the wall surface that crystallise. The effect can be cyclical with salts going back into solution when the internal relative humidity rises and then being redeposited.

Rainwater penetration can be caused by poor workmanship. An example is where roof tile laps are reduced by stretching the gauge during retiling to economise on materials. This will increase the chances of moisture penetration, including as a result of wind-driven rain or ingress by melting snow on roof slopes.

Poor detailing can also cause dampness. Cold spots from gaps in insulation are conducive to condensation. Roofs on porches or extensions may be of inferior quality, with poor weatherings and rainwater disposal.