Find out more about our products by giving us a call

0333 987 4452

0333 987 4452

Tuscan Foundry Products, Tyn-Y-Clyn, Llanafan Fawr, Builth Wells, Powys LD2 3LU, United Kingdom

© Tuscan Foundry Products 2022

Introduction

St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral is a Gothic Revival Anglican church located in Western Edinburgh. Since its construction between 1874 and 1879 by the great George Gilbert Scott, as a response to the exponential urbanisation, moral and religious developments of the period, it has served the Christian community relentlessly over the years. A structure of the Gothic style, it is a bold statement during Edinburgh’s era of classical revival with the development of an ‘Athens of the North’. It displays various features that identify it as Gothic revival, yet it also embraces Scott’s unique interpretation, as well as various contributions by others. There is a general consensus among the Cathedral’s inspiration and its influence within Edinburgh and Scotland. However, the focus is seemingly on the initial impression of the Cathedral from the exterior, with very little discussion of the interior’s impression. The intention is to investigate the Cathedral’s impact within Edinburgh, as well as the recognition Scott received – is he deserving of this or is it purely an exaggeration?

Many historians agree that Gothic revivalism arose from a period of instability and revolution. The Napoleonic Wars and the Industrial Revolution proved highly influential in the development of a new moral dimension which combined Victorian ideals, religion and a desire to return to the ‘harmonious’ middle-ages.[1] However, Brittain-Catlin wanted it to be noted that rapid urbanisation and growing wealth meant both demand for churches and increasing restoration/construction funds also contributed to this form of medieval revivalism.[2] Many other historians also note this rapid expansion, including Fletcher, contributing to the development of Edinburgh’s New Town from around 1766 to 1850,[3] involving domestic, secular and religious construction.

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book (2005), 12.

Desmarest, Clarisse Godard (ed.). 2019. The New Town of Edinburgh: An Architectural Celebration. Edinburgh: 2019); John Donald, Carter Mckee, Kirsten. Genius Loci of the Athens of the North: The Cultural Significance of Edinburgh’s Calton Hill. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: 2014). http://search.proquest.com/docview/1827469158/?pq-origsite=primo; Lowrey, John. From Caesarea to Athens: Greek Revival Edinburgh and the Question of Scottish Identity within the Unionist State. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 60 (2), 2001: 136–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/991701.

Glendinning, Miles. St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide (2003).

Fazio, Michael W, Marian Moffett, and Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. Third edition (London: Laurence King, 2013), 3; Brooks, Chris. The Gothic Revival (London: Phaidon Press, 1999). https://contentstore.cla.co.uk/ secure/link?id=6302b6b6-8529-eb11-80cd-005056af4099. 5.

Brittain-Catlin, Timothy. ‘Chapter 79. Britain and Ireland, 1830–1914’. In Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture, Vol 2, edited by Murray Fraser (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018) 601-640.

Fletcher, Banister. Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture. Volume 2. British Isles, 1500–1830 Edited by Murray Fraser. 21st edition (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018).

Similarly, many historians consider Pugin to be the driving force behind the movement, promoting the gothic style for all buildings (secular and public), with his book ‘Contrasts: Or, A Parallel Between The Noble Edifices Of The Middle Ages And Corresponding Buildings Of The Present Day’ (1836) inspiring the Gothic revival across Britain and especially George Gilbert Scott, who also regarded him highly, recognising him as a ‘guardian angel.’ Brittain-Catlin also adds that Pugin offered a clear, individual design; a solution to the inefficiencies of Neoclassicism in the era of the development of the ‘athens of the north’. Like the other historians, Brittain-Catlin acknowledges the new religious/moral aspect within Gothic revivalism, considering Pugin to be at the forefront of this development. Yet some historians imply Scott to be more prolific and popular than Pugin in the development of Gothic revivalism.

Discussions of the design process are limited among historians. However, there seems to be a general consensus that no expense or detail was spared in its design. From the exotic wood of the organ’s casing and choir stalls, to the modern materials of wrought iron and vast expanses of stain glass, the Cathedral’s fine furnishings are somewhat an impressive contrast against the cold solidity of the masonry.

Most historians focus purely on Scott’s work, thus disregarding the contributions made by others since. Although the design is Scott’s alone, many of the features that make the Cathedral so unique are the work of others, lesser known to the world. Glendinning, in particular, notes these characteristics, discussing the Cathedral as an evolving landscape rather than a completed feature as others like St. Mary’s Cathedral do.

There is consistency in the belief of the lasting influence exerted by the Cathedral’s founders Mary and Barbara Walker among the historians, through commemorative windows and artwork. Even the western spires are named after them.

Several of these sources are from the Cathedral Board, perhaps focusing on its impression and standing within the Cathedral community, hence the immense detail on the elaborate, if a little excessive design and thoughtful placement. Meanwhile, Glendinning is an accomplished academic with expertise in Scottish architecture. Therefore, he is well-placed to discuss the Cathedral in its city context as well as its inspiration and influence from within Scotland. His argument is supported by quality images, including plans and interior images. Stamp may show some bias towards GG Scott, as implied through his thoroughly admirable tone, yet he also discusses potential inspiration for Scott and the declining popularity of Gothic revivalism by throughout the period of the Cathedral’s construction.

Fazio, Moffett, Wodehouse, A World History of Architecture,14.

Stamp, Gavin. Great Scott! A Gothic Reputation Is Revived. Building Design (Tonbridge: CMP Information Ltd, 2011), 28.

St. Mary’s, Cathedral. An Exhibition of Sir George Gilbert Scott 1811-1878: Architect of St. Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh: In the Cathedral Chapter House: St. Mary’s Cathedral Centenary Year (1979), 11.

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book, 12; St. Mary’s Cathedral, St Mary’s Cathedral: History of the Erection of the Cathedral Church of S. Mary, Edinburgh; Glendinning, Miles. St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide, 2.

Stamp, Great Scott! A Gothic Reputation Is Revived, 29.

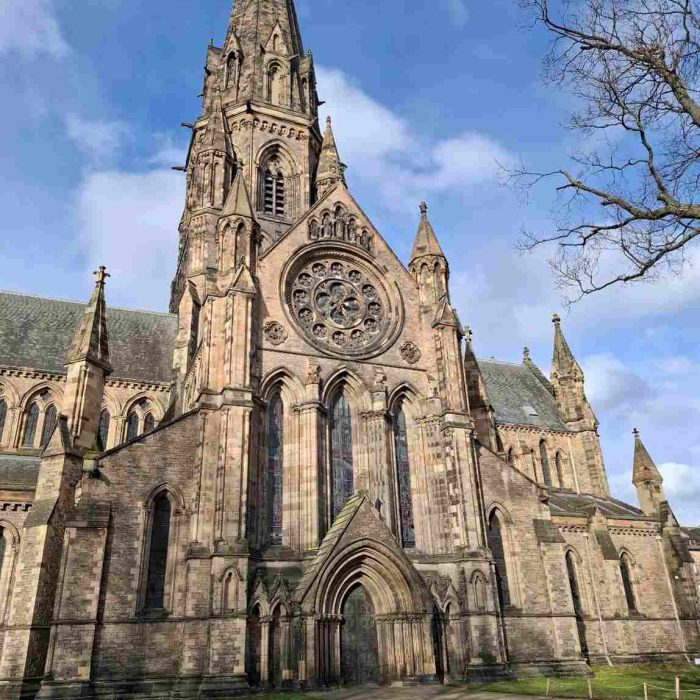

St Mary’s is a bold statement on the skyline of Edinburgh. The solid, vertical form of freestone stands boldly among the rigidity of the surrounding Georgian streets, with its three spires reaching to the heavens (figure 1).

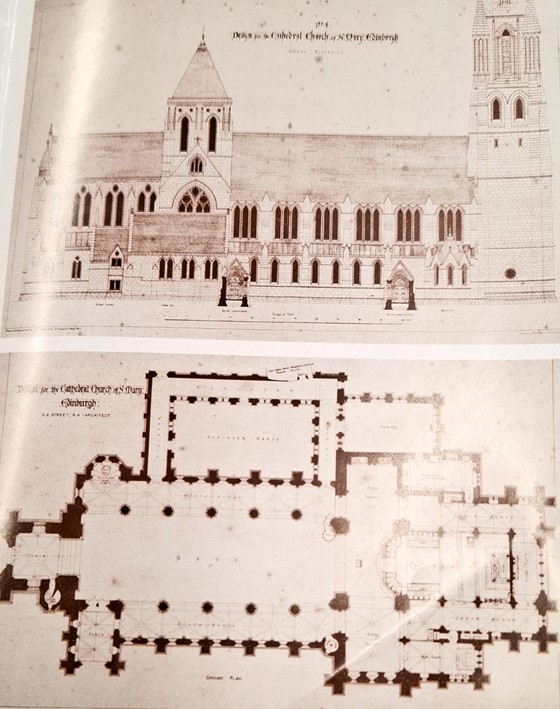

Located at the western end of Melville Terrace, the Cathedral’s axis aligns with its centre – the main entrance is from Palmerston Place. It has a cruciform plan with a central tower, considered by many historians to be a significantly desirable feature in a cathedral (figure 2 below).

Figure 1. View of St. Mary’s from Palmerston Place (author’s own, 2025).

Figure 2. The cruciform plan and North elevation showing the central tower (Glendinning, 2003).

The book by St. Mary’s Cathedral itself considers the style to be inspired by the early Gothic churches and abbeys of Scotland. Others develop this further, believing Holyrood Abbey specifically inspired both the plan, form and features of St. Mary’s. The same book from 1879 also implies that inspiration also came from Northern England, where the architecture of Scotland and Northern England was united by this early phase in pointed architecture. The Cathedral is part of a complex; functional buildings such as the stonemasons’ workshop, Walpole Halland Song School shown below in figure 3.

Figure 3. showing the Cathedral’s outbuildings (author’s own, 2025).

Scott attempted to make the Cathedral itself as large as the site allowed. The floor space measures a significant 80m by 40m, and Scott didn’t suppress its verticality either, with a central tower and spire of 90m and the western spires reaching 60m. The Western spires were a later completion (1913-17) by Scott’s grandson and named after the Cathedral’s founders Mary and Barbara Walker. These spires frame the entrance and were intended to create the ‘most imposing gothic façade’ ….‘severe in purity, dignified in its elegant proportions and rich in elaborate carved work’. This intention is displayed in figure 3 below. Despite being designed by Scott’s grandson, the Western spires follow the typical GG Scott design – an octagonal tower arising from a square base. Similarly, the chapter house (figure 4) follows the same style, by another of Scott’s followers, Hugh James Rollo.

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book, 2-5.

St. Mary’s Cathedral, St Mary’s Cathedral: History of the Erection of the Cathedral Church of S. Mary, Edinburgh, 13.

Glendinning, St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide, 2-5.

Figure 3. The bold, intimidating form that is St Mary’s (author’s own 2025).

Figure 4. The typical GG Scott style of an octagonal structure arising from a square base and merging into a spire/roof as displayed in the chapter house and spires (author’s own, 2025).

Interior:

The interior showcases the lightness and verticality associated with old-gothic forms, although the decoration is simpler with greater focus on emphasising the structural finesse. An open columned arcade of alternating octagonal and rounded columns flanks the central nave, with a complex compound of columns differentiating the chancel. This is shown below in figures 5a. and 5b. The ceiling above the nave is constructed from timber, supported by clustered shafts from corbels placed high up on the walls. This contrasts the chancel where concrete and stone ribbed vaulting emphasise verticality.

Figure 5a. Showing the open columned arcade (author’s own, 2025).

Figure 5b. Showing the alternating rounded and octagonal columns (author’s own, 2025).

Few historians discuss Scott’s unique interpretation of the Gothic style, which incorporated illusions and deceptive features, agreeing that he instead followed the typical Gothic design of centuries previous. However, Glendinning highlights Scott’s unique translation of the style, with the deceiving curvature of the apse due to its connection with the chancel roof (figure 6). Similarly, the octagonal towers which arise from square bases and merge into spires are acknowledged to be a distinctive feature of Scott’s work by both acknowledged to be a distinctive feature of Scott’s work by both Glendinning and St. Mary’s Cathedral.

Glendinning, St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide, 2-5.

Figure 6. Shows the deceiving nature of the apse (author’s own, 2025).

Various materials are used within the interior, particularly for the collection of furnishings added since its erection. Most furnishings are the work of Scott himself, and his son J Oldrid Scott. However, there are some major exceptions:

Various memorials and sculptures fill the vast interior and walls, especially the south aisle, with its dedications to Scottish nobility and military personnel. The north aisle has a series of stain glass windows depicting the life of Christ as well as commemorative windows of GG Scott. There is also a millennium window on the South wall designed by Eduardo Paolozzi.

Glendinning, St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide, 2-5; St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book, 5-7.

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book, 16.

Ibid,11-12.

The Rood Cross was added in 1922, as a war memorial by R S Lorimer. It depicts a figure of Christ in a field of Flanders poppies and hangs over the threshold between the nave and crossing (figure 7).

Figure 7. The view from the chancel towards the great entrance with the Rood Cross hanging above the threshold (author’s own, 2025).

Glendinning, St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh A Short History and Guide,1.

The Gothic-renaissance style organ by Henry Willis is encased in mahogany, (figure 8) whilst grey limestone forms the edging of the chancel steps and diamond floor tiles of the chancel (figure 9). Various cretaceous fossils can be seen in the limestone with closer observation. The choir stalls are walnut with carved plant and animal motifs (figure 10), as identified by both Glendinning and St. Mary’s Cathedral Scottish Episcopal Church Guide Book.

Originally a set of 10 bells by Taylors of Loughborough hanging in the octagonal bell chamber above, a further two were added in 2008.

Figure 8. The baroque-renaissance style organ (1879) by Henry Willis with its mahogany encasing (author’s own, 2025).

Figure 9. Shows the limestone-edged diamond floor tiles (author’s own, 2025).

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book, 12.

Figure 10a. and 10b. The walnut choir stalls with plant and animal motifs (author’s own, 2025).

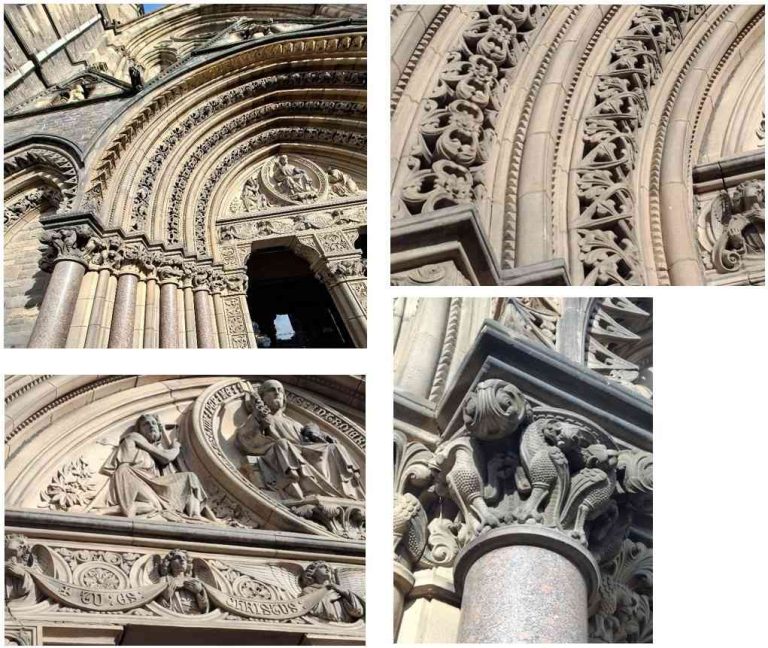

The exterior boasts typically Gothic features, both functional and aesthetic. Buttresses, not clearly visible, support the momentous mass of the central tower (figure 11) along with its ring of 12 bells, the second-heaviest ring in the world. The tower is flanked by carved pinnacles at each corner, and the portal of the great doorway is richly moulded, similar to Holyrood Abbey. Above the western portal sits a pointed arch (figure 12), deeply recessed within its wall. The window itself contains four arched windows, each lancet divided by clustered mullions with a large wheel window above. Details that can be found on this façade include: sculptured angels, a carved cross-crowned gable and dog-tooth ornament. These features are shown in figure 13 a,b,c and d below.

Glendinning, St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide (2003), 2-5.

St. Mary’s Cathedral, St Mary’s Cathedral. History of the Erection of the Cathedral Church of S. Mary, Edinburgh (1879),13.

Figure 11. Showing the southern entrance with the spire flanked by its pinnacles behind (author’s own, 2025).

Above the southern entrance, a rose window standing 24ft in diameter implies of lightness of structure, yet its tracery is less delicate and elaborate than typical old-gothic windows. Once again, dog-tooth ornament and sculptured angels are a feature of this façade, as well as carved crosses atop the gables and three lancet windows.

Each section of the façade is regular and rather plain, with windows and arches placed in regular intervals. The majority of ornament is found on the towers and portals of the entrances.

Figure 12. Shows the Great Entrance (western) flanked by the twin spires. The wall boasts a deeply recessed pointed arch along with a large wheel window (author’s own, 2025).

Meanwhile, features defining the gothic style such as pointed arches, gargoyles and ornate mouldings line the exterior walls, as shown in the series of figures below. However, ornate carvings in the masonry and elaborate tracery are found to be more subdued in the Gothic Revival style of St Mary’s, in comparison to its fellow early Gothic counterpart, St Giles’ Cathedral in the city centre.

Figures 13 a,b,c & d. show the elaborate carved stonework surrounding the Great Entrance (author’s own, 2025).

St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral is a distinguished, contrasting structure of its era, where architecture of antiquity dominated. It takes inspiration from traditional Scottish churches and abbeys, uniting the architecture of Scotland and the North of England. A response to urbanisation and population growth, it is able to serve hundreds of locals in its impressively vast space. No thought or expense was spared in its design, reflecting the meticulous planning of the ordered Georgian streets of the New Town, respecting its context but not an attempt to replicate it. Despite some subtle unique features by GG Scott, the interior is what makes St Mary’s truly unique, with its contrasting materials, and exquisitely deliberate details. Therefore, despite Stamp’s persuasive argument of Scott’s influence, one could argue that the building’s evolution since has contributed to its distinguished character more so than Scott himself, agreeing with Glendinning’s argument. St Mary’s argue that the major feature of the Cathedral is its initial curb impression, yet the sheer vastness of space within, the contrasting materials, elaborate details and stunning stained glass windows one could argue are the distinguishing elements of the build.

The memorials and commemorative pieces within are evidence of the pride shown towards contributors and its status, and in particular the founders Mary and Barbara Walker as discussed by various historians. Meanwhile, although the historians agree upon the Cathedral’s significance in style, it perhaps should be viewed as a masterpiece of its time, with a lower standing in the present day, socially, architecturally and religiously than originally intended by the founders and Scott himself.

Banister Fletcher. Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture. Volume 2. British Isles, 1500–1830 Edited by Murray Fraser. 21st edition (London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2019).

Brittain-Catlin, Timothy. ‘Chapter 79. Britain and Ireland, 1830–1914’. In Sir Banister Fletcher’s Global History of Architecture, Volume 2, edited by Murray Fraser (London: Bloomsbury Publishing Plc., 2019). 601-640.

Chris Brooks. The Gothic Revival (London: Phaidon Press, 1999). https://contentstore.cla.co.uk/ secure/link?id=6302b6b6-8529-eb11-80cd-005056af4099.

Clarisse Godard Desmarest, (ed.). The New Town of Edinburgh: An Architectural Celebration. Edinburgh: 2019).

Gavin Stamp. Great Scott! A Gothic Reputation Is Revived. Building Design (Tonbridge: CMP Information Ltd, 2011).

John Donald, Kirsten Carter Mckee. Genius Loci of the Athens of the North: The Cultural Significance of Edinburgh’s Calton Hill. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing: 2014): http://search.proquest.com/docview/1827469158/?pq-origsite=primo.

John Lowrey. From Caesarea to Athens: Greek Revival Edinburgh and the Question of Scottish Identity within the Unionist State. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 60 (2), 2001: 136–57. https://doi.org/10.2307/991701.

Michael W Fazio, Marian Moffett, Lawrence Wodehouse. A World History of Architecture. Third edition (London: Laurence King, 2013).

Miles Glendinning. St Mary’s Episcopal Cathedral, Edinburgh: A Short History and Guide (2003).

St. Mary’s, Cathedral. An Exhibition of Sir George Gilbert Scott 1811-1878: Architect of St. Mary’s Cathedral, Edinburgh: In the Cathedral Chapter House: St. Mary’s Cathedral Centenary Year (1979).

St Mary’s Cathedral. St Mary’s Cathedral: Scottish Episcopal Church: Guide Book (2005).

Study Document By: Eliza Stenning

Edinburgh University – First Year Architecture Student

Cast iron offers an authentic appearance that complements traditional architecture. It’s also robust, long-lasting, and often required to meet listed building consent conditions. Unlike plastic alternatives, cast iron guttering retains the historic integrity of a building and weathers beautifully over time.

It’s also worth noting that modern cast iron systems benefit from factory-applied protective coatings, making them easier to maintain and install than in decades past. Cast iron offers seamless integration into any historic elevation when matched carefully to the existing system or surrounding details.

Sales & Customer Services:

0333 987 4452

Tyn-Y-Clyn

Llanafarn Fawr

Builth Wells

Powys LD2 3LU

United Kingdom

Tuscan Foundry Products, Tyn-Y-Clyn, Llanafan Fawr, Builth Wells, Powys LD2 3LU, United Kingdom

© Tuscan Foundry Products 2022